In my entire career as a student of Architecture, and for the past ten years working as a Set Designer in film, I have somehow (thankfully) managed to avoid AutoCad. For those of you unfamiliar with this program which is also known as CAD (Computer Aided Design or Computer Aided Drafting), it’s a software application for 2D and 3D design and drafting. It was developed and sold by Autodesk beginning in 1982, it was one of the first CAD programs to run on personal computers (notably the IBM PC), and it has become the foundation standard for all architectural documents produced around the world.

I can remember taking my AutoCad course in university in 1998 and hating every second of it. Something about it just rubbed me in such a bad way I made a decision to never touch it again. Certainly if I had pursued a life in the world of architecture I would have had no choice in the matter, but over the past ten years in film I’ve managed to uphold the classical values and methodology that inspired me so much when I was a student and avoid the program entirely. So when I read articles like the one I just found in Slate this morning where legendary architect Renzo Piano lashes out at what has become of the industry it only confirms what I’ve felt all along:

Surely this march of progress is all to the good. Who would want to go back to the days before pencils and tracing paper? But the fierce productivity of the computer carries a price—more time at the keyboard, less time thinking. The thumb-nail sketch — an architectural staple since at least the Renaissance — risks going the way of the T-square. “But architecture is about thinking. It’s about slowness in some way. You need time,” Renzo Piano said in an interview last year. “The bad thing about computers is that they make everything run very fast, so fast that you can have a baby in nine weeks instead of nine months. But you still need nine months, not nine weeks, to make a baby.” Some teaching programs have taken steps to remedy, or at least mitigate, the situation. Yale has a summer program in Rome in which students are required to sketch by hand. McGill University continues to require classes in freehand life drawing and sketching school in the summer. The University of Miami introduces computers only in the second year of its program. This is not a question of turning back the clock but, rather, of slowing it down—and recognizing that rigor of thought is as much a part of design as making shapes.

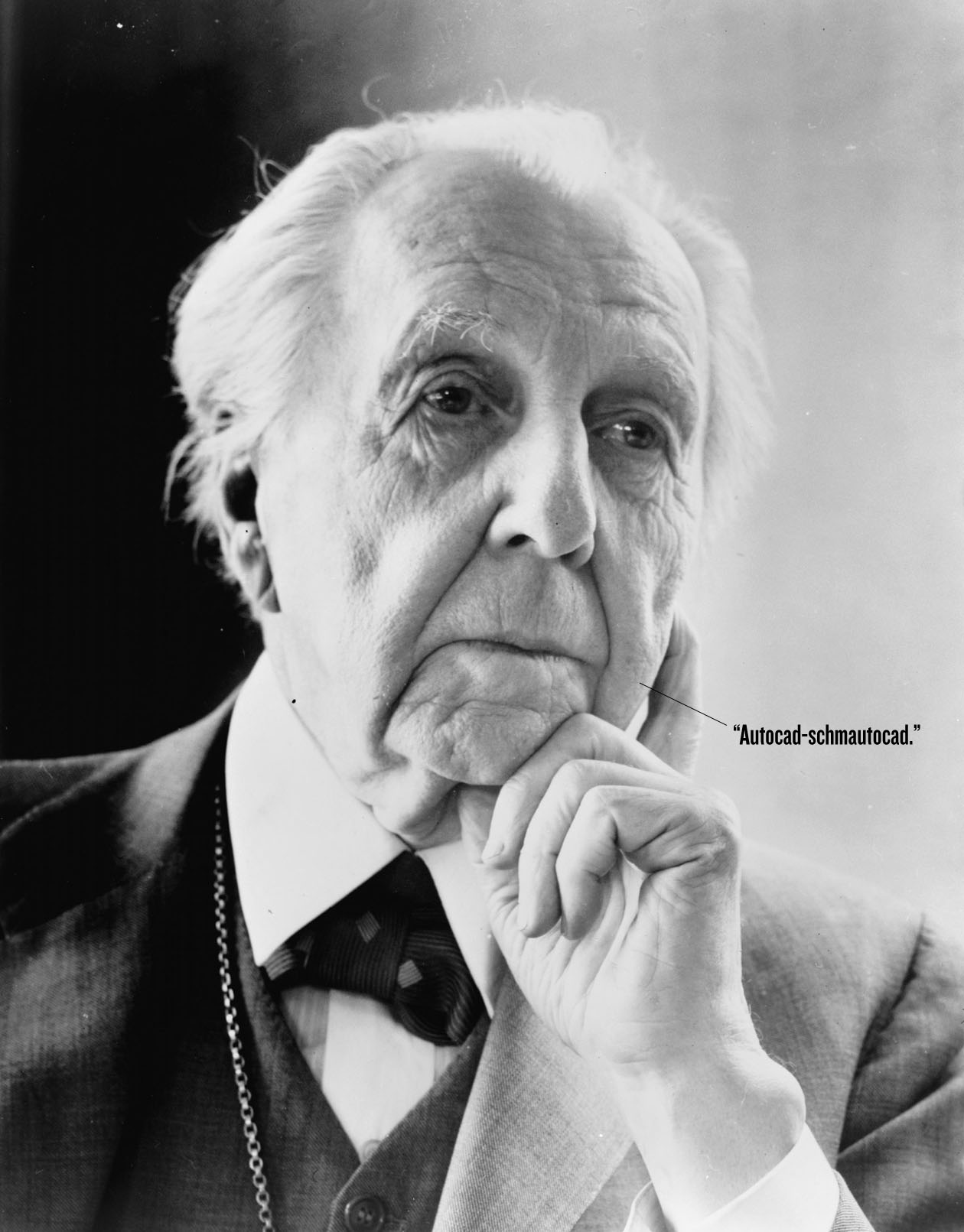

You can read the full article by Witold Rybczynski over at Slate, and you can also click on the word “interview” in the quoted text above for the original Renzo Piano interview. Incidentally, last night I was having dinner with my friend Nico, a fellow architecture grad and film colleague, and we were talking about the story of Frank Lloyd Wright’s design development for the Fallingwater house, undoubtedly the most significant and influential modern home design in the world. It’s a fascinating story and it gives a wonderful glimpse into a design process that not only changed architecture forever, but had nothing to do with a computer whatsoever:

Source: Slate

Source: Slate