Eleanor Roosevelt will forever remain one of the most towering figures in the American pantheon of powerful women who changed the course of history. Never one to bow to male dominance and power, Eleanor Roosevelt had more balls, bravado, and boldness in her pinky finger than most men have in their entire body. And she readily made mincemeat of any man who dared force her to change her convictions. So when she became First Lady in March 1933 — a role which usually meant disappearing into the shadow of the President — she kicked it off by defying tradition and holding the first-ever First Lady press conference, weeks before her husband Franklin D. Roosevelt had his first.

What’s more, Eleanor invited only women reporters to the event, and handed out candies to her guests at the opening welcome. A few months later in July, when summer was in full swing, Eleanor defied Secret Service orders and she fulfilled a personal dream she’d always had to see Quebec City and visit the renowned natural wonderland of the Gaspé Peninsula along Quebec’s east coast where the mouth of the gigantic Saint Lawrence River opens up to meet the Atlantic Ocean. Ditching convention, Eleanor refused to take any staff or security with her — just her best friend and press secretary, Lorena “Hick” Hickok. The following is an excerpt from chapter 8 of writer Bill Young‘s terrific book, Eleanor Roosevelt: A Personal and Public Life, which describes the now legendary road trip.

“Eleanor made herself more accessible to the public than any previous First Lady. But at the same time she fought to preserve a private realm, where she could simply be herself. She refused to be accompanied on her travels by Secret Service agents and insisted on driving her own car without a police escort. The heads of the Secret Service fretted – kidnappers had recently killed Charles Lindbergh’s child, and that winter an assassin in Miami had fatally wounded Chicago’s Mayor Cermak as he stood beside Franklin. Nonetheless, Eleanor continued to value privacy above safety, and refused protection. Finally. a frustrated Secret Service agent placed a gun on Louis Howe’s desk and told him to make the first Lady carry it. Eleanor took the gun, and with Earl Miller’s help she learned to shoot it, but there her compliance ended: she carried it unloaded in her glove compartment.

During the summer of 1933 Eleanor tested the bounds of her liberty, as if to determine just how much of her private life she could preserve in her new position. First she purchased a car: not a staid black Lincoln or Cadillac as might befit the First Lady of the land, but a light blue Buick roadster, a sporty convertible with a rumble seat. The car was a whim, to lose herself in the formal persona of President’s wife. As if to proclaim her freedom from convention, Eleanor indulged in other whims. She had always wanted to watch the sunrise from Vermont’s Mount Mansfield and drive around the Gaspe Peninsula and spend a night in a tourist home. Why not do these things and more? The children had their own summer plans, the White House social season was over, Eleanor was only forty-nine, and life was still an adventure. In this frame of mind she invited Hick to join her in the roadster for three weeks traveling as “ordinary tourists” through New York, New England, and Eastern Canada. The Secret Service was aghast, fearing that the First Lady would be abducted.

That idea amused Eleanor as she and Hick sped north in the convertible with the wind whistling in their ears. Eleanor was nearly six feet tall and Hick weighed nearly 200 pounds. “Where would they hide us?” Eleanor demanded. “They certainly couldn’t cram us into the trunk of a car!” As the sun dipped toward the Adirondacks and dusk fell over the forested countryside, they passed a little house with a sign welcoming tourists. “Let’s go back and try it,” Eleanor said, “I’ve always wanted to stay in one of those places.” The owners – a young couple with a small-baby – were startled to see Mrs. Roosevelt walk through their door. But Eleanor behaved like an ordinary tourist, and the hostess, regaining her composure, showed the guests to an ordinary room, small but spotless. The hot-water system was not fully installed, she explained, and so there was water for only one bath.

Alone, Eleanor and Hick argued over who would use the tub. “You’re the First Lady, so you get the first bath,” said Hick. Eleanor playfully thrust out her long fingers at her friend as if to tickle her into submission. Hick, ticklish but persistent, finally won, and Eleanor bathed. But with her spartan upbringing, she managed to take her bath cold, and Hick found to her surprise that the tap water was still warm. That night before they went to sleep Eleanor read to Hick from one of her favorite books, Stephen Vincent Benet’s John Brown’s Body.

The next morning they visited John Brown’s farm and his grave near Lake Placid. With three weeks to themselves they traveled slowly toward Canada, criss-crossing the Green Mountains of Vermont and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. One evening they found themselves in a small town at the foot of Mount Mansfield. It was pitch black, and the village policeman advised them not to attempt the treacherous mountain road in the dark. But Eleanor was determined to see the sunrise from the top. The roadster whined up the trail in low gear, its headlights falling on trees and then into open space as the car rounded hairpin turns on the way to the Green Mountain Inn and a short night’s rest.

A few hours later Eleanor and Hick watched the early morning sunlight that broke over the Atlantic and struck the mountains of northern New England. Atop Mount Mansfield they saw the light catch the mountain peaks and drop slowly into the valleys of the silent wilderness; far to the north they could see Mount Royal in Canada, and to the west Lake Champlain caught the pure light of dawn. To the south, out of sight beyond the horizon, the sun brightened the White House and the Washington Monument, five hundred miles away in space, further still in thought.

The women drove on into Canada, staying at the majestic Chateau Frontenac in the old stone city of Quebec. For the next few days they drove along the south bank of the St. Lawrence on one of the loveliest roads in all of North America. She and Hick ate meals cooked over woodburning stoves, lay under the sun on a warm beach, and swam in the St. Lawrence. America seemed far away, and their anonymity complete. They stopped at a little church by the water, and the village priest invited them to lunch in his rectory. Hearing Eleanor’s name he asked her: “Are you any relation to Theodore Roosevelt? I was a great admirer of his.”

“Yes,” said Eleanor, smiling, “I am his niece.”

Eleanor and Hick spent their last night in Canada at a tourist camp in a trim log cabin with a huge stone fireplace. The next day they crossed the border into Maine. For the past few days, Eleanor had delighted in her freedom. She had not been the First Lady of America; she had been an ordinary person – herself. But that must soon end. With the convertible top still down, looking disheveled with white sunburn cream smeared over their faces, they drove into the town of Presque Isle, where to their “horror” a parade awaited them. They were “wind-blown, dusty, and dirty” and Eleanor felt anything but gracious. But she was trapped and fell dutifully into line with the procession that moved slowly down the main street between rows of flag-waving children. A portable traffic standard loomed ahead and a flustered Eleanor clipped it. “Damn,” she said.

This was the only time Hick ever heard her friend swear. Eleanor may have been surprised at her own profanity, but she managed to drive on through the town. When she realized that a dozen or so cars were still following them, she told Hick, “We’ve got to get out of this some way.” The First Lady then sped around several comers and lost her escort on a country road in the potato fields of Aroostook County. Here they saw a farmhouse with a sign welcoming tourists.

After registering they settled their nerves with a walk and then sat on a porch swing. Soon the farmer appeared and sat on the steps. Eleanor began talking knowledgeably about potato prices and local agricultural conditions. The farmer’s wife came out and sat in a rocking chair; as darkness settled over the farm land, the four of them went on talking. Hick sensed the farmer’s wowing admiration for Eleanor. At about eleven o’clock they went into the kitchen for a snack of doughnuts and milk. In their room Hick asked Eleanor how she had managed to know so much about farming in Maine. Eleanor explained that she had read a local newspaper; she also gained information from the farmer as she went along: “something I learned to do when I was very young,” she said, “to cover my ignorance.” She might also have mentioned Franklin’s coaching. He had taught her to be a good observer while he was Governor of New York, and he would need her reports even more now that he was President.

After a short visit to Campobello, Eleanor and Hick drove back to Washington. On the night of their return Franklin began a tradition he would observe throughout his Presidency: he dined informally with Eleanor so that she could tell him what she had learned. Hick told him about Eleanor’s altercation with the traffic standard, and Franklin’s “great, booming laugh” filled the room. Franklin asked about the country they had seen. What was the hunting and fishing like in Quebec, he wondered. How did the people live: what were their houses like, what did they eat, did the Catholic Church control education? And what about Maine: how were the farmers getting along, what had she learned about the Indians? Eleanor answered these questions and others. It was soon apparent to Hick that although Eleanor had relaxed on their vacation, she was constantly registering information for herself and for Franklin, even making mental notes about the state of laundry hanging on clothes lines – any detail that would help them both understand more fully the condition of the nation they served.

In such ways Eleanor brought together her private and her public life, even while touring in a Buick convertible. The vacation had been an escape from Washington, a part of Eleanor’s personal life; at the same time it served her public role and her relationship with Franklin. The personal distance between Eleanor and Franklin remained great. He could relax more easily with Missy and Anna than with his wife. In the White House there were rooms enough for the President and First Lady each to have their own suites. When guests came for dinner, they often had cocktails with Franklin or with Eleanor in their separate White House apartments, before coming together for dinner.”

You can learn more details about Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1933 road trip from the White House to Quebec by visiting the Montreal Gazette.

.

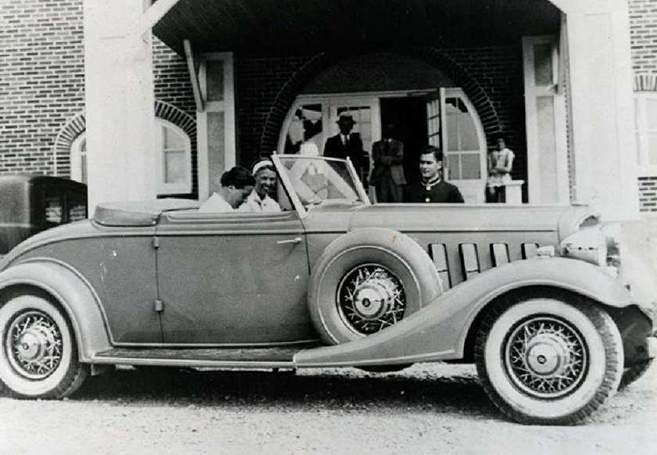

PHOTO 1 BELOW: Eleanor Roosevelt (behind the wheel) with her best friend Lorena Hickok at the Hotel Belle Plage in Matane, Quebec on July 15 or 16, 1933. (Photo courtesy of The Historical and Genealogical Society of Matane, via Montreal Gazette)

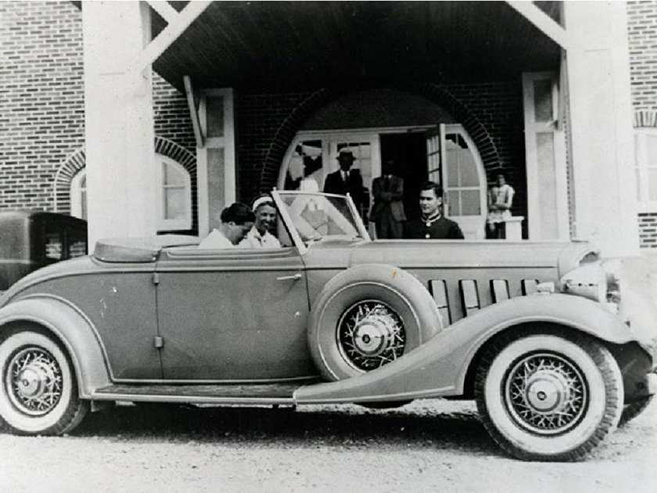

PHOTO 2 BELOW: (left to right) Quebec Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, Lorena Hickok, Eleanor Roosevelt, Lieutenant Governor Henry George Carroll (with staff in back row) after a lunch at Bois-de-Coulogne, Quebec on July 12, 1933. (Photo credit: W.B. Edwards, courtesy of Martin Edwards, via Montreal Gazette)

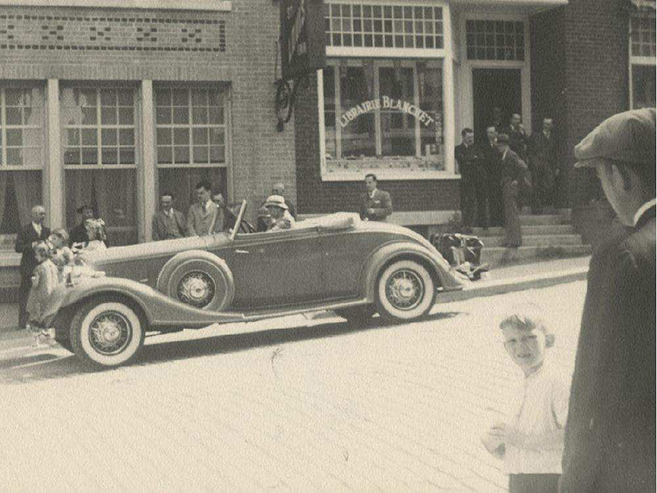

PHOTO 3 BELOW: Eleanor Roosevelt (behind the wheel) with Lorena Hickok, on Lafontaine Street in Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec on July 14, 1933. (Photo courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, thanks to Florentine Films, via Montreal Gazette)

PHOTO 4 BELOW: Eleanor Roosevelt (second from left), Lorena Hickock on far right (Photo courtesy of United States National Archives, via American Realities)

INTERACTIVE MAP: courtesy of Lee Nilson, with text from Bill Young’s Eleanor Roosevelt: A Personal and Public Life