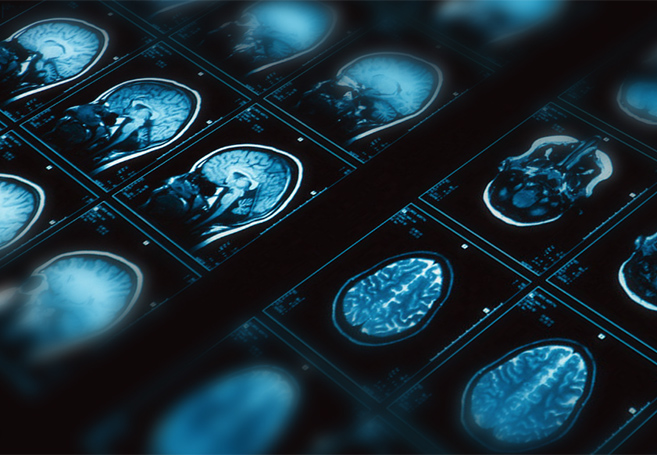

A new global interdisciplinary study has discovered that persistent depression shrinks the brain’s hippocampus –- the headquarters of our emotional center and memory. Fifteen research centers from the United States, UK, and Australia joined forces for the research and results were published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry on June 30th.

“This study confirms – in a very large sample — a finding that’s been reported on quite a few occasions — the fact that the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to depression,” explains Philip Mitchell, science professor & head of the School of Psychiatry at University of South New Wales, Australia, who participated in the research. The hippocampus is also responsible for attaching emotions to memories, as well as being a major force in long-term memory processes. “Your whole sense of self depends on continuously understanding who you are in the world — your state of memory is not about just knowing how to do Sudoku or remembering your password — it’s the whole concept we hold of ourselves,” says professor Ian Hickie, from the University of Sydney’s Brain & Mind Research Institute, who spearheaded the Australian portion of the study. “When you shrink the hippocampus, you don’t just change memory, you change all sorts of other behaviors associated with that — so shrinkage is associated with a loss of function,” Hickie adds.

65% of the study’s test subjects had smaller hippocampuses due to recurrent bouts of depression, as well as early-onset depression (before the age of 21). “I think this resolves for good the issue that persistent experiences of depression hurt the brain,” says Hickie. “Those who have only ever had one episode do not have a smaller hippocampus, so it’s not a predisposing factor but a consequence of the illness state. The more episodes of depression a person had, the greater the reduction in hippocampus size. Recurrent or persistent depression does more harm to the hippocampus the more you leave it untreated.” The key to preventing brain damage lies in early treatment, and the study also found that patients who were taking antidepressants had a larger hippocampus. “There is a lot of nonsense said about antidepressants that constantly perpetuates the evils of them, but there is a good bit of evidence that they have a protective effect,” said Hickie. “[Antidepressants] are not the only treatment — a broad range of treatments [should] be explored. [Psychotherapy] must be explored as the first line of treatment, not medicines.”

In related news, a new study published in Nature has found that happy memories have a stabilizing effect on one’s overall mood, akin to insulin’s effect in regulating blood sugar. “Stress can induce depression, and the hippocampus regulates cognitive aspects of this response. [Hippocampal] neurons that were active during a pleasant experience were genetically labelled in mice. Subsequent exposure of these mice to chronic immobilization stress resulted in depression-like behaviours that were transiently attenuated.” You can read more about the first study by visiting Nature.com and by CLICKING HERE. (Photo courtesy of National Geographic).

SEE ALSO: New Research Discovers That Depression Is An Allergic Reaction To Inflammation

SEE ALSO: A Newly Discovered Pearl-Size Region In The Brain Appears To Be Ground Zero For Depression

SEE ALSO: Anxiety, Depression & Autism 100% Linked To Gut-Brain Axis And An Abnormal Microbiome In Intestines

.