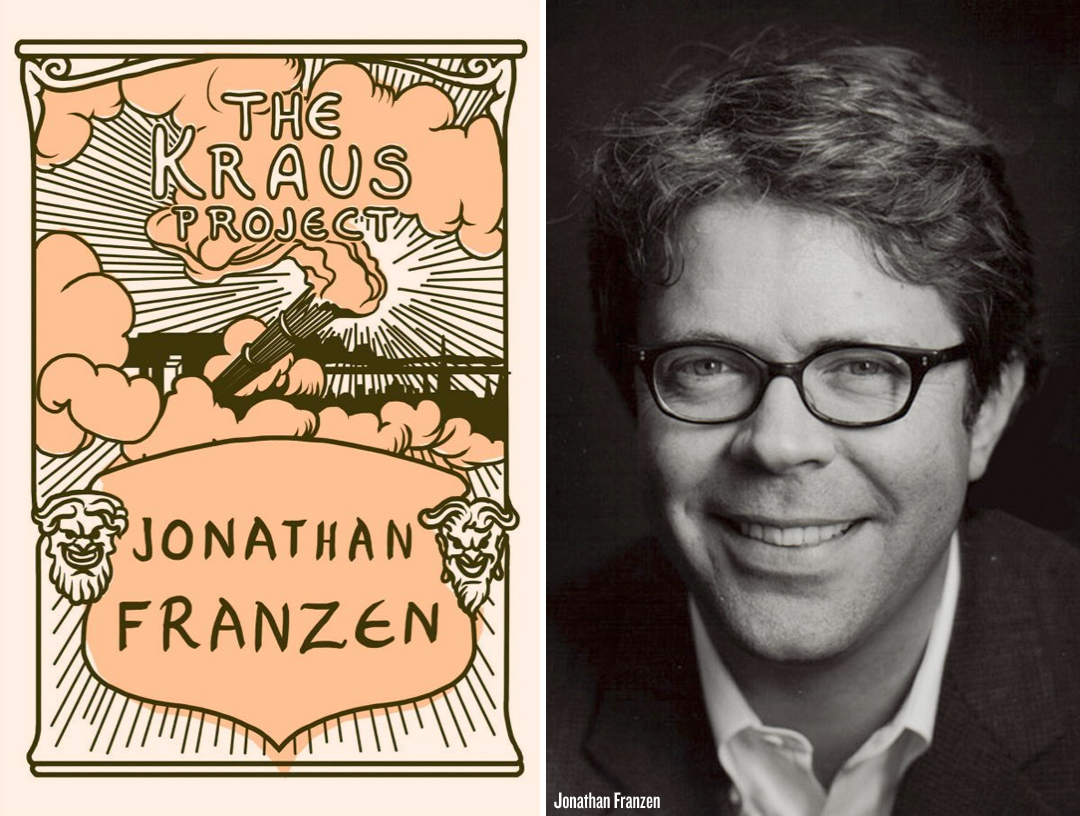

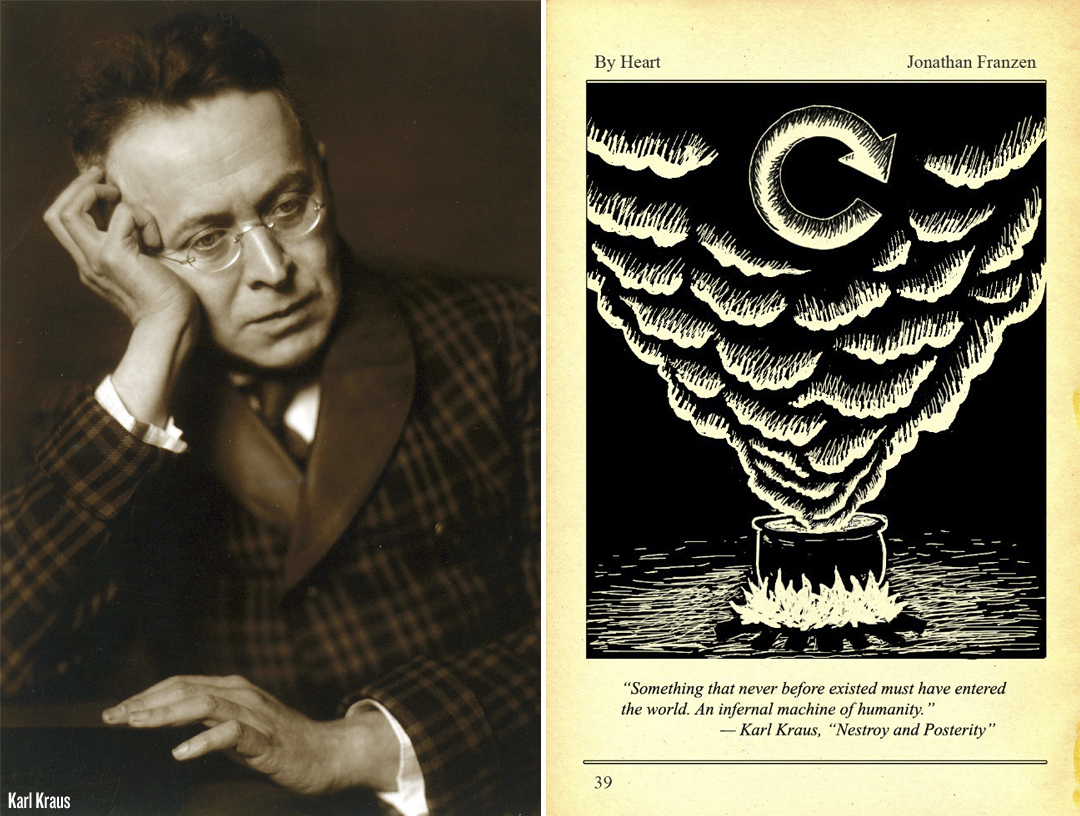

Jonathan Franzen is the acclaimed American writer behind such award-winning novels as Freedom, and The Corrections. With a longstanding reputation as being one of America’s most reclusive and private writers, Franzen understandably has a tense relationship with the new era of online technology where everything is made public instantaneously, and there is no such thing as an “internal monologue”. In a brilliant new feature story published in The Atlantic, Franzen elaborates on why he feels the Internet is not necessarily carrying our civilization to a better place. Franzen frames his argument with the help of one of his favorite writers — Karl Kraus, the Austrian satirist, playwright, and critic of the mass media, was born in 1874 and ran the magazine Die Fackel (“The Torch”) from 1899 until his death.

Franzen explains why one quote from Kraus, in particular, captured his imagination: “One of the lines from Kraus that matters the most to me is ‘Ein Teufelswerk der Humanität,’ an ‘infernal machine of humanity.’ In the mid-’90s, when I started to feel worried about what was happening to literature with the introduction of the third screen, and with the increasingly materialistic view of human nature that psychopharmacology was producing, I was looking for some way to describe how technology and consumerism feed on each other and take over our lives. How seductive and invasive but also unsatisfying they are. How we go back to them more and more, because they’re unsatisfying, and become ever more dependent on them. The groupthink of the Internet and the constant electronic stimulation of the devices start to erode the very notion of an individual who is capable of, say, producing a novel. The phrase I reached for to describe all this was ‘an infernal machine.’ Something definitionally consumerist, something totalitarian in its exclusion of other ways of being, something that appears in the world and manufactures our desires through its own developmental logic, something that does damage but just seems to keep perpetuating itself. The sentence that summed this up for me owed a lot to Kraus’s writing: ‘Techno-consumerism is an infernal machine.'”

Franzen continues by quoting the second most powerful quote he has ever read from Kraus: “We were smart enough to build the machines, but not smart enough to make them serve us.” In Franzen’s view, the Internet has certainly provided us with certain social benefits, but not without destroying other important elements that are vital to a strong and vibrant culture. Journalism, for example, is in the process of being wiped out, and no healthy civilization can exist without a strong network of talented and committed journalists busy making those in power honor their word. And from a more personal perspective for Franzen, the Internet (especially social media) is creating a society where everything is shared 24 hours a day — to our detriment. For a novelist, Franzen explains, it is important to maintain a healthy diet of solitude and introspection. In a world of 24-hour sharing, however, it makes it increasingly difficult for our writers and novelists to “go deep” and come back to tell us what they have learned. Franzen adds: “What I find particularly troubling about our own technological moment is that I hear people saying again and again — happily and proudly and excitedly — that computers are changing our notion of what it means to be a human being. The implication of all those excited people is that we’re changing for the better. Whereas, when I look at social media, it seems like a world that once had adults in it is being changed into the 8th grade junior-high cafeteria. When I look at Facebook, I see a video-poker room in Vegas.”

You can read Jonathan Franzen’s entire essay by visiting TheAtlantic.com. His thoughts expressed here come from his brand new book The Kraus Project: Essays by Karl Kraus, in which Franzen annotates Kraus the way Kraus annotated others. Franzen surveys today’s cultural and technological landscape with fearsome clarity, and gives us a deeply personal recollection of his first year out of college, when he fell in love with Kraus’s work. Painstakingly wrought, strikingly original in form, The Kraus Project is a feast of thought, passion, and literature. You can purchase your own copy of the book via Amazon.

As a counterpoint to Franzen’s critique of the Internet and the social media monster it has unleashed, I have included the inverse argument made by one of Franzen’s most renowned contemporaries — award-winning Canadian author, Margaret Atwood. Atwood has become an unlikely superstar of the Twittersphere, and in a recent CBC News interview for her book MADDADDAM, Atwood explains how Twitter is not a threat to literature in the least. You can watch the entire insightful interview in full below. Acclaimed American author, Joyce Carol Oates, is another example of a renowned writer who has embraced the power of Twitter. Both of these women make it clear that social technology by no means impacts a writer’s creative output — it only adds to it. You can follow Margaret Atwood on Twitter, as well as Joyce Carol Oates on Twitter as well.

As a footnote, lately I have found myself obsessed with all things Joyce Carol Oates, which is why I’m attaching another interview where the celebrated author discusses one of her recent books — her first memoir — where she writes about the painful loss of her husband of nearly 50 years. You can fast forward to the 11:00 mark to get to the beginning of the interview where Oates discusses the story behind A Widow’s Story: A Memoir (Amazon, 2011). This is one of the most remarkable conversations I have seen in as long as I can remember.

SEE ALSO: FEELguide Editorial: Is Facebook Destroying The Mystery, Miracle, And Adventure Of Being Alive?