In 2013 it is nearly impossible to be engaged in modern life without encountering and interacting with brands. The presence and implications of brands have not only become interwoven with our national identities and cultures (i.e. Apple = America, NHL = Canada, Hermes = France, etc.) they affect our own individual sense of self as well. From the shoes you wear, to the car you drive, to the dishware on your table, to the websites you frequent, to the music you listen to, to the films you watch — often times we don’t even realize that our choices of what we consume end up having an enormous impact on how we make sense of ourselves and our place in the world around us.

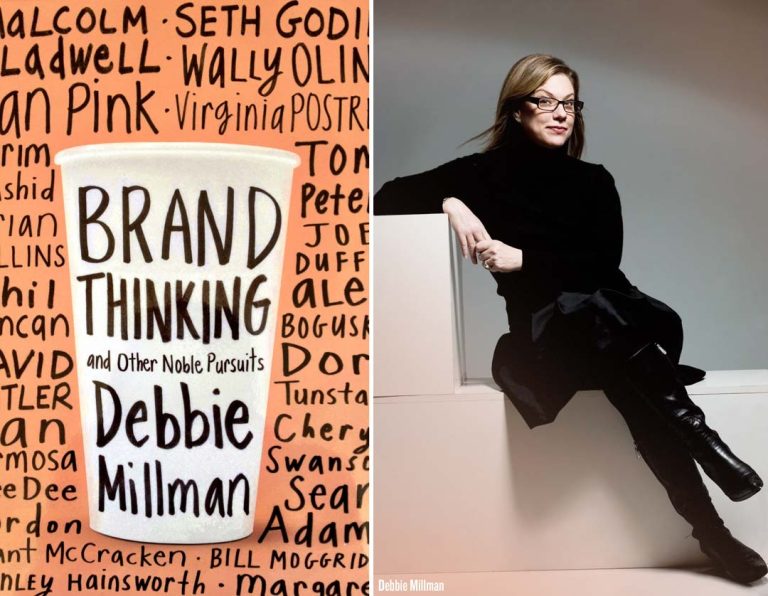

In Debbie Millman’s fascinating new book Brand Thinking And Other Noble Pursuits, the philosopher, artist, design guru, and host of the radio show Design Matters explores the psychology, function, and impact of brands in our everyday lives. Millman interviews such luminaries as Malcolm Gladwell, Karim Rashid, Daniel Pink, Seth Godin, Alex Bokusky and many more for their wisdom and insights into the fascinating, yet oftentimes uncomfortable realm of our personal relationships with brands. Brain Pickings recently put together a terrific compilation of some of the book’s highlights, and these are just a few:

SETH GODIN: I believe that “brand” is a stand-in, a euphemism, a shortcut for a whole bunch of expectations, worldview connections, experiences, and promises that a product or service makes, and these allow us to work our way through a world that has thirty thousand brands that we have to make decisions about every day … The reason we keep refreshing the way so many things look is because of our ceaseless race to leverage the feelings of safety and nostalgia this old thing imparts, while simultaneously injecting a sense of newness to seduce us into reengaging in the experience … Workaholics are driven by fear, and I have not found myself in a position where I need to spend six or eight more hours at work because I’m trying to make everything okay … If you’re in this frame of mind and need control, being a workaholic is a socially acceptable way to try to achieve that. Your boss thinks it’s great, and you can get a raise for doing it. In the short run, it works really well because you can — at some level — control what you’re doing and keep pushing the ball forward. You get into trouble when you get better at your work, and there’s an increase in the number of people who want to interact with you and have you do more. So this kind of working method doesn’t scale— you end up exploding. The people who are doing great art and having an impact on the world aren’t approaching their work in this way. I recently did an interview with the architect Michael Graves. Michael Graves works a lot. He’s been in a wheelchair for more than seven years. He would be excused if he decided to scale back now after what’s been an amazing career. But, instead, he’s working on a multibillion-dollar development in Singapore, etc., etc. If you look at the way Michael works, he brings a good heart and the right attitudes to his projects at all times. He is doing important work — work that changes things. But he’s not a workaholic because he’s not doing it defensively. He’s doing it productively.

ALEX BOGUSKY: If you’re afraid of mediocrity, you have to push past wherever mediocrity lives. A lot of people believe that there is a right and there is a wrong, and that there are creative rules. I think that trying to figure out what’s the right or wrong way to do things is a form of fear. This inhibits people, and holds them back. In creative departments, you need to create a culture where you can break lots of rules.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I have the same feeling toward the word “brand” as I do toward the word “Africa.” “Africa” is an incredibly problematic word for me. It’s a word used with great frequency to describe an intricately complex area made up of people, countries, and cultures that have no more in common than we do with Uzbekistan. But because it’s a convenient word, and a well-known word, and a geographically defined continent, we use that word to sum up and generalize everyone who lives within the continent. In a way, it really is unfair. But we’ve inherited that framework, and I think we’d be better off if we banned the word entirely. Getting back to “brand,” the word has similar implications. Yes, it’s of much smaller consequence — it’s a trivial example of the same problem, but it is a problem. The word gets thrown around so recklessly that I wonder whether we wouldn’t be better off setting it aside. Instead, if we could use more specific words that zero in on what we’re really interested in discussing, it would help the conversation.

You can read the entire feature profile and “Best Of” compilation of Millman’s book by visiting BrainPickings.org. And to pick up your own copy of Debbie Millman’s Brand Thinking And Other Noble Pursuits via Amazon. Millman’s radio show Design Matters earned the prestigious Cooper Hewitt National Design Award in 2011. For more great story discoveries from Brain Pickings that I’ve shared on FEELguide CLICK HERE.