Smell is the grandfather of all senses; the oldest one, in fact, with its origins coming from the rudimentary senses for chemicals in air and water — senses that even bacteria have. Before vision or hearing and even before touch, creatures first evolved to detect and react to the chemicals around them. Vision relies on 4 kinds of light sensors (receptors), touch relies on at least four receptor types, but smell relies on a more staggering number — at least 1,000 different smell receptor types that will regenerate throughout your lifetime.

The olfactory bulb is the part of your brain responsible for processing smells, and it happens to be located right beside the hippocampus. As the BBC writes: “This name means ‘seahorse’, and the hippocampus is so-called because it is curled up like a seahorse, nested deep within the brain, a convergence point for information arriving from all over the rest of the cortex. Neuroscientists have identified the hippocampus as crucial for creating new memories for events. People with damage to the hippocampus have trouble remembering what has happened to them.” Knowing this, it already makes perfect sense for smell and memory to have an intimate connection — but the connection get far more interesting. Smell is exceptionally unique among the senses because of its special place deep inside the brain. All other senses must first pass through the brain’s “customs and border inspection” station known as the thalamus, before passing on to the rest of the brain.

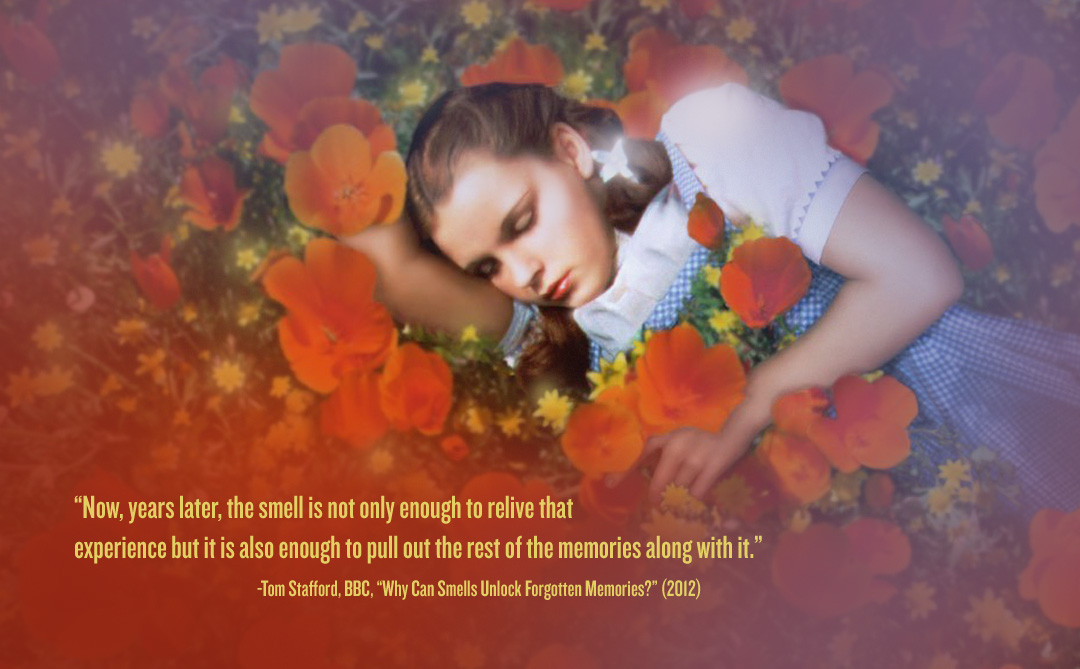

Why does smell require such presidential V.I.P. treatment? First try the following thought experiment: try and describe a complex fragrance in words. It is nearly impossible; however, with all other sights it is extremely easy. It is no coincidence that the non-V.I.P. senses which must first pass through the thalamus are easy to describe in words, while smell — which has direct proximity to the hippocampus, the part of your brain responsible for encoding experiences — is not. Memory research has revealed that describing things in words can assist memory, but it also reduces the emotion we feel about the subject. The memories our brain stores with regards to vision, touch, hearing, and taste are each compartmentalized and stored independently. Memories associated with smell are infinitely more complex, having been stored so close to entangled with a treasure trove of non-sensory, emotion-based memories which are often long forgotten and stored deeeeeeeeeeep in the attic of your brain. Something as simple as recalling a smell from your youth has the power to pull out with it other memories — some of which have been deeply hidden for years, often decades — which have glued themselves to that one particular fragrance you just recalled from ages ago. To read a fascinating story of what happened to BBC’s Tom Stafford who picked up on a long-forgotten smell from his grandmother’s cupboard be sure to visit BBC Future.