When I was about 10-years-old I made myself sick by eating too many stale cheeseballs. To this day I still can’t pass a bag of them in a store without dry heaving. And I’m afraid the same thing is happening — this time with Facebook. Something has happened to the world’s largest social network over the past few months that has turned me off it in a major way. I now use it almost strictly as a river/stream of news and postings from my favorite brands/organizations, and I’ve turned off most of the people I’m tired of listening to. Why waste a good spot on my News Feed with a whiner when I can get a Forbes update in its place?

And it appears I’m not alone. New research coming out of the University Of Waterloo is showing that Facebook has now been around long enough that people are becoming more aware of how annoying certain “friends” are. The study centered on 3 factors: 1) confidence, 2) emotional expression, and 3) Facebook curation, and was designed by University of Waterloo graduate student Amanda Forest and her adviser, Joanne Wood. For the study, the test subjects (all undergrad students) were assessed with a standard self-esteem test and placed on a spectrum from MORE to LESS confident (NOTE: when asked what they thought of Facebook, those with lower confidence were likelier to describe the site as a safe space in which friendships were unencumbered by awkward face-to-face interactions). Forest and Wood then collected the 10 most recent status updates from each of the many people who were assessed.

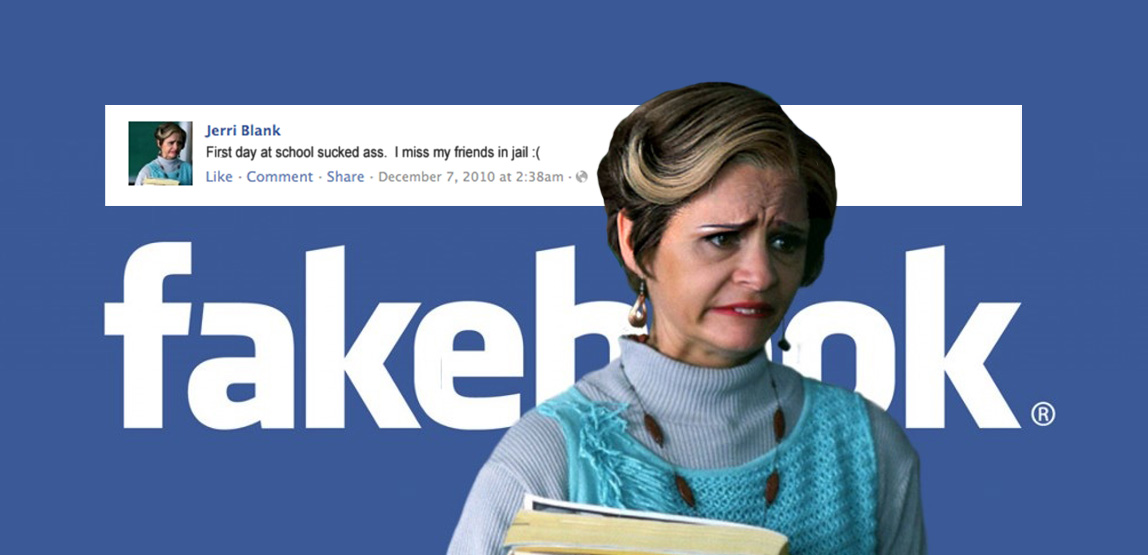

Those with the least confidence tended to post updates such as: “Why does this always happen to me?! Once again, the universe has bitchslapped me.” While the more confident subjects would post updates such as: “So happy to have so many incredible friends! This is going to be an incredible week!”

Another large group of undergraduate students was brought together to read the batches of status updates and rate how much they liked (or didn’t like) the strangers who wrote them. Turns out that these volunteers were immediately turned off by the unconfident complainers who groaned continuously and often played the “victim card” in their outlooks on life; while the status updates showing the most confidence generated the highest favorable reactions.

As Katy Waldman of Slate commented in her recent column which profiled the study: “I find these results oddly heartbreaking. It seems an irony typical of the Internet that the people who feel safest expressing themselves online actually damage their social standing when they do so. Not because they’re somehow opting out of the real world, as Facebook critics like to insist, but because they are lulled into relaxing their facades. Cheery icons and a shiny, sanitized format make it easy to project the friendliness of a diary onto the Facebook community. Yet the site doesn’t ‘change’ your audience so much as disguise it. Those with low self-esteem may treasure Facebook because it eliminates situations in which social feedback is inevitable (whereas you can’t help seeing your friend’s aggrieved expression when you slip up in person). But you need live feedback to teach you to navigate relationships with grace.” She also adds: “Social networking sites, with their endlessly personalized apps, can sometimes feel less like meeting places than giant mirrors (Facebook for me has always had the echoey effect of a mansion that a crowd of partiers has just vacated). Amanda Forest’s study should remind us that when we’re online, for better or for worse, we’re not alone.”

For all things Slate be sure to visit Slate.com and follow them on Facebook. For a complete archive of all of Katy Waldman’s columns CLICK HERE.