FEELguide Editorial | by Brent Lambert (January 26, 2011): It’s safe to assume that the vast majority of people consider themselves to be reasonably “good” people. Perhaps, for instance, you recently gave a donation to Doctors Without Borders, or you lovingly call your mother every weekend, or this morning you rinsed out your yogurt container so that Mr. Recycler won’t have to do it himself when it arrives at the processing plant. As further proof of your noble constitution, you can also say that you have never carried out an assassination attempt on a member of Congress like Jared Lee Loughner did when he shot Rep. Gabrielle Giffords on January 8, critically injuring her, as well as killing six others, and injuring fourteen more. The results of this tragedy would certainly have been much worse had it not been for the four heroes present: the two men who tackled Loughner after he fired, the woman who snatched the ammunition magazine out of Loughner’s hand during the tackle, and Giffords’ intern whose coincidental past experience in triage almost certainly saved his boss’s life.

If one were to carry out an anthropological survey of all moral and immoral acts committed by human beings throughout history, from the most saintly assassin-tackler to the most insane gunman, it would have a range of shades from dark to light, 0%-100%. If we assume this to be true, the question raised is this: where exactly would your own moral average rank in this spectrum? An interesting place to begin the search for this answer within yourself might be your reaction to the Trolley Paradox. Consider the following two situations:

SITUATION #1: You are at the wheel of a runaway trolley quickly approaching a fork in the tracks. On the tracks extending to the left is a group of five railway workmen. On the tracks extending to the right is a single railway workman. If you do nothing the trolley will proceed to the left, causing the deaths of the five workmen. The only way to avoid the deaths of these workmen is to hit a switch on your dashboard that will cause the trolley to proceed to the right, causing the death of the single workman. Is it appropriate for you to hit the switch in order to avoid the deaths of the five workmen?

SITUATION #2: A runaway trolley is heading down the tracks toward five workmen who will be killed if the trolley proceeds on its present course. You are on a footbridge over the tracks, in between the approaching trolley and the five workmen. Next to you on this footbridge is a stranger who happens to be very large. The only way to save the lives of the five workmen is to push the stranger off the bridge and onto the tracks below where his large body will stop the trolley. The stranger will die if you do this, but the five workmen will be saved. Is it appropriate for you to push the stranger onto the tracks in order to save the five workmen? 1

This paradox has sparked a great deal of head-scratching because SITUATION #1 is arguably a no-brainer, whereas SITUATION #2 is considered by many to be reprehensible. A team of researchers led by Harvard Professor of Psychology, Joshua Greene, discovered through the use of fMRI that the more personally-involved SITUATION #2 caused intense stimulation in the emotion centers of the subjects’ brains who chose not to kill the fat man [In an interview with ABC News, Giffords’ intern, Daniel Hernandez, explained that he would never had been able to help her had it not been for his ability to “shut off all emotion.” 2]. Another team discovered that people’s responses to each situation can be modulated (i.e. subjects who spent a few minutes watching a pleasant video before the experiment showed a higher likelihood of pushing the fat man to his death). 3

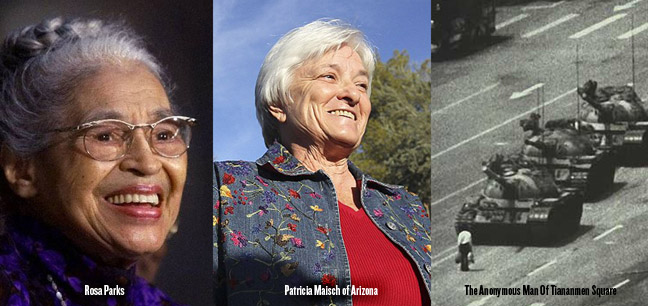

If you were to push the fat man off the bridge and, as a result, end up saving the lives of so many people, is it safe to assume that your face would be on the front page of every newspaper and website in the world with the word “HERO” in bold typeface written above? If Patricia Maisch, the 61-year-old Tucson woman who grabbed the magazine from Loughner, had shot the psychopath with a gun of her own would she still be labelled a hero? Publicly no, but privately in minds around the world probably yes. This seems to prove two things: PROOF A) our reaction to SITUATION #2 can vary depending on our mental state (and I would add by our collective life experience as individuals), and PROOF B) our society’s qualifications for what determines whether an act is classed as heroic appear to be affected by the laws of the state. [An intriguing notion to PROOF ‘A’ would be if the actions of the four heroes in attendance that fateful day in Arizona were in any way influenced by having watched Giffords speak prior to the shooting; in the same way the subjects of the Trolley experiment changed their reaction to SITUATION #2 by having watched a pleasant video beforehand. And furthermore, what about a possible SITUATION #3: Would you throw yourself off the bridge to save the lives of five strangers?].

In order to gain an understanding of the inner workings of a hero’s (or a psychopath’s) mind we need to get down to the scientific nuts and bolts. If one were to peek inside the brain chemistry of both the assassin and the hero(es), what would we discover? We have a tendency to think of a hero as a very special type of human being: people whose altruistic impulse is so intense that they are even willing to sacrifice their own life to save another, seemingly the exact opposite of a madman. Fascinating research, however, is revealing that not only is the extreme-altruism (X-altruism) personality not the exact opposite of the sociopathic personality, rather, it is shockingly similar.

In fieldwork conducted by Watson, Clark, and Chmielewki from the University of Iowa, “Structures Of Personality And Their Relevance To Psychology”, the team was led to these surprising conclusions . As Andrea Kuszewski describes in her essay The Rogue Neuron where she looks at the results of the Iowa study, she explains, “X-altruists are compelled to good, even when doing so makes no sense and brings harm upon them. They cannot tolerate injustice, and go to extreme lengths to help those who have been wronged, regardless of their personal relationship to them. Now, I am not speaking of the guy who helps an old lady cross the street. I am speaking of the guy who throws himself in front of a speeding bus to push the old lady out of the way, killing himself in the process. The average, kind, thoughtful person does not take these kinds of extreme personal risks on a regular basis. When they are faced with that moment, they just act. Compulsively. Barely considering any other course. They have no problem breaking the rules when it means helping an innocent, yet they highly value the importance of obeying rules in other contexts. That’s crazy, you say? Now you’re getting the idea. The X-altruistic person is anything but passive or meek. They are often feisty, argumentative, independent, idealistic risk-takers and convention-breakers.”4 Here’s how the results of the study broke down:

SOCIOPATH: low impulse control, high novelty-seeking (desire to experience new things, take more risks, break convention), no remorse for their actions (lack of conscience), inability to see beyond their own needs (lack of empathy), willing to break rules, always acts in the interest of himself.

EXTREME HERO (X-ALTRUIST): low impulse control, high novelty-seeking, little remorse for their actions (would “do it again in a heartbeat”), inability to see past the needs of others (very high empathy), willing to break rules, acts in the best interest of others, or for the “common good” (because it is the right thing to do).5

The sociopath, therefore, is driven by internal factors (i.e. selfishness with zero empathy, such as Jared Loughner or a militant Islamic suicide bomber), and the extreme hero is driven by external motivations (selflessness with too much empathy which can result in death such as the anonymous man who risked his life by blockading the tanks of Tiananmen Square in 1989 or the passengers of United 93). As Kuszewski explains, “Because [the hero] often engages in such extreme behavior that results in harm to self on some level, he or she earns a spot on the dysfunctional end of the personality scale, nearing psychopathology.”6 Before a tragedy unfolds that engages the empathy factor in either the sociopath or the X-alturist, their personalities can often be indistinguishable. “These two type of individuals, the sociopath and the X-altruist, may appear similar in their displays of behavior, and at times, even confused for the other type. If an X-altruistic person is compelled to break rules without remorse in order to help a disadvantaged person, is may seem as if he is acting rebelliously, especially if the motives behind his behavior are not known. On the other hand, a sociopath may donate a large sum of money to a charity, a seemingly altruistic behavior, but his actions may have been motivated by his selfish need to appear better than or more generous than a colleague. The defining characteristic that separates the two personality types is their ability to empathize, either not at all or too much, which then drives the extreme behavior of each. So while the X-altruistic person indeed acts for the good of the people, he or she often violates laws, breaks rules, or otherwise causes ripples in the order of society.”7

The results of the Iowa study focus on the two extremes of our “empathy spectrum”. What it doesn’t focus on are the “mid-spectrum” heroes of everyday life. Notice how Kuszewski readily admits these people were not included in this personality research, “I am not speaking of the guy who helps an old lady cross the street. I am speaking of the guy who throws himself in front of a speeding bus to push the old lady out of the way, killing himself in the process.” Therefore the following people were not part of this study: the teacher in Brooklyn who paid for her students’ new text books out of her own pocket when the board said there was no money in the budget, or the residents of Thomasville who came together to support Donna Brady and her two little boys after her husband died in a car accient. One might also add Rosa Parks to this list, who in 1955 refused to give up her seat to a white person, thereby sparking the Civil Rights movement (although I would argue she, too, was putting her life at risk based on the lynchings and Ku Klux Klan activity occurring in Alabama at the time, thereby ranking her closer to 100% X-altruism. She may not have been directly jeaopardizing her life at that very second, more so indirectly jeopardizing it in the future. Perhaps she would be ranked at 99%?). And from what I’ve gathered, the four heroes present at the Giffords shooting don’t necessarily fit the personality profile of the X-altruist either. They probably lie somewhere between the central spectral zone and 99% empathy.

So what was it that made the ordinary citizens that comprised “The Giffords Four” react so courageously? What would we see if we peeled back the veils of their more typical brains? Like the majority of human beings, they appear to be hardwired with empathy. A sort of built-in sixth sense: the moral sense. In the collective worlds of neuroscience, evolutionary biology, evolutionary psychology, and other similar fields, researchers are unlocking the secrets of this innate moral code in all of us with fascinating results. No longer are we chained to archaic religious texts to find the answers to the most profound questions regarding morality. Any religious person who claims that if the Ten Commandments did not exist the world would be ravaged by rape, murder, and theft, is arguing an untenable claim. One of the world’s leading intellectuals, Christopher Hitchens, effortlessly exposed the impotence and hypocrisy of these rules and those who created them in his famous Vanity Fair essay “The New Commandments”. One of my favorite portions of Hitchens’ argument deals with Commandment #10:

“THOU SHALT NOT COVET THY NEIGHBOR’S HOUSE, THOU SHALT NOT COVET THY NEIGHBOR’S WIFE, NOR HIS MANSERVANT, NOR HIS MAIDSERVANT, NOR HIS OX, NOR HIS ASS, NOR ANY THING THAT IS THY NEIGHBOR’S. There are several details that make this perhaps the most questionable of the commandments. Leaving aside the many jokes about whether or not it’s O.K. or kosher to covet thy neighbor’s wife’s ass, you are bound to notice once again that, like the Sabbath order, it’s addressed to the servant-owning and property-owning class. Moreover, it lumps the wife in with the rest of the chattel (and in that epoch could have been rendered as “thy neighbor’s wives,” to boot).” (You can read Hitchens’ essay or watch him debunk the other nine commandments in this Vanity Fair video HERE).

Hitchens has also been positing the following challenge for years which, as of today, continues to go unanswered: “Tell me of a moral action performed or an ethical statement made by a believer that I couldn’t make because I’m a nonbeliever. You ought to be able. Given what you think, it must be very easy for you to say, here’s something you couldn’t say or do that would be morally right or morally true. No takers; I haven’t found a single example.” He continues this challenge with a corollary that each and every time it is asked manages to amass a tsunami of examples: “Name me a hideous immoral act undertaken or an immoral remark made by someone because of their faith.” This list would probably stretch from Arizona to Mount Sinai. Hitchens believes — as would anyone with a rational mind — that, “Morality is not learned by orders. It’s acquired by experience, by moral suasion, and by comparing and contrasting different ways of resolving these questions.”8

One is on much safer ground if they direct their search for answers away from theology and towards the kind of logic described above, and towards the scientific community as a whole which is busy excavating these truths from not just the human mind, but also from other animals. As Steven Pinker pointed out in a New York Times essay in 2008, “The impulse to avoid harm, which gives trolley ponderers the willies when they consider throwing a man off a bridge, can also be found in rhesus monkeys, who go hungry rather than pull a chain that delivers food to them and a shock to another monkey. Respect for authority is clearly related to the pecking orders of dominance and appeasement that are widespread in the animal kingdom. The purity-defilement contrast taps the exact same emotion of disgust that is triggered by other stimuli such as potential disease vectors like bodily effluvia, decaying flesh and unconventional forms of meat, and by risky sexual practices like incest.”9 In other words, we seem to be hardwired with the understanding that behaving immorally or committing an immoral act can be harmful to us. And in a separate series of experiments, Frans De Waal writes in his New York Times article “Morals Without God?”, “Such observations fit the emerging field of animal empathy, which deals not only with primates, but also with canines, elephants, even rodents. A typical example is how chimpanzees console distressed parties, hugging and kissing them, which behavior is so predictable that scientists have analyzed thousands of cases. Mammals are sensitive to each other’s emotions, and react to others in need.”10

Perhaps the most renowned (human being) obedience study in history was conducted in 1971 at Stanford University and led by Philip Zimbardo, considered by many to be the most famous psychologist in the world, and one of the sharpest observers of human behavior in extreme circumstances. Zimbardo and his team carefully selected 24 random college students from across America (the students were each expertly-diagnosed as being 100% psychologically normal with zero mental health issues or concerns). As Russell Weinberger explains in Edge: The Third Culture, “The students were randomly assigned to roles of prisoners or guards in a mock prison located in the basement of the psychology building at the university. The results were shocking. Within days, the ‘guards’ turned authoritarian and sadistic while the ‘prisoners’ became passive and started to show signs of severe depression. What was supposed to be a 2-week experiment had to be shut down after only six days.”11 Known simply as the Stanford Prison Experiment, it led Zimbardo to write his iconic book “The Lucifer Effect”. The results of the study were blisteringly clear: human nature is as malleable as silly putty, and the wrong situation can bring out the worst in anybody — even the most perfectly normal college student. It can also reduce this same healthy young man to a trembling puddle of weakness on a prison cell floor in less than one week. [Worth nothing is there was no Rosa Parks-esque revolt initiated by any of the twelve ‘prisoners’, but if this experiment were to be repeated multiple times (although human rights laws would likely prohibit this experiment from ever being conducted again in most countries) we likely would find a prisoner brave enough to rise up to mad, unregulated authority.]

Nazi Germany is the most horrific example of The Lucifer Effect in modern times. Eventually, once this demonic fire of epic proportions had been extinguished in 1945, the guilty stood trial in Nuremberg. In her now classic analysis of evil, Hannah Arendt had stood present at the tribunal of Adolf Eichmann, one of the men responsible for cooperating in the genocide. After the trial was over, Arendt and other specialists in her field were given the task of analyzing Eichmann and his counterparts in order to find out what made these monsters tick, and what made them capable of committing such hellish acts to begin with. The results were mind-boggling. After the guards were studied, Arendt and the other experts determined, at least in the case of Eichmann, that he was perfectly normal. One of the analysts even went so far as to say, “He’s more normal than I am. He’s a good father, good husband, good citizen.”12 Arendt herself said, “he was so terrifyingly normal that this was a new kind of monster – a monster that we are not prepared to face and fight because he looks just like us.” Her Nuremberg studies led her to coin the term “the banality of evil”.13

Zimbardo is often asked about the Eichmann model and its implications, and in an interview with Weinberger, Zimbardo responds, “My research really says several things. One, that we have to recognize that some situations, some social settings, some behavioral contexts, have an unrecognized power to transform the human character of most of us. Two, that the way to resist – the way to prevent a descent into Hell, if you will – is precisely by understanding what it is about those situations that gives them transformative power. It is by this understanding that you can change those situations, avoid those situations, challenge those situations. And it’s only by willfully ignoring them, by assuming individual nobility, individual rationality, or individual morality that we become most vulnerable to their insidious power to make good people do bad things. Those who sustain an illusion of invulnerability are the easiest touch for the con man, the cult recruiter, or the social psychologist ready to demonstrate how easy it is to twist such arrogance into submission.”14

The results of the experiment were so disturbing to Zimbardo that he has since made a 180º course correction in his career by devoting his life to study the heroic end of the spectrum instead of the psychopathic. No longer concerned with what makes an assassin pull a trigger, or why we so easily fall into madness when locked up in an orchestrated basement power dynamic (he notes that there is a mountainous body of research on this side of the coin but an almost non-existent body on the heroism side), he is now using his expertise to help nurture heroic behavior in our society. He qualifies there as being two types of heroes in our world: “life-long” heroes such as Mandela, Tutu, and Gandhi; and “situational” heroes like The Giffords Four, or Joe Darby, the army reserve MP who exposed the torture that was occurring at Abu Graib. Zimbardo says, “My sense is that the typical notion we have of heroes as super-stars, as super heroes, as Superman, and Batman, and Wonder Woman, gives us a false impression that being a hero means being able to do that thing which none of us can actually accomplish. I want to argue just the opposite: that what we have to be doing more and more is cultivating the ‘heroic imagination‘ – especially in our children.”15

So how do we as a society foster this “heroic imagination”? Many would eagerly jump once again to religion as our best option. But it can be argued that the net value of all the religious charitable work and goodness that exists in our world is negated by the moral intuitions that religion obscures. Let’s take stem cell research as just one example. The human embryos that are harvested for stem cell research are three days old, and at this stage they consist of roughly 150 cells. You might think this is a significant number, but when you consider that a fly’s brain contains 100,000 cells it pales in comparison. If your concern is about suffering then it should make perfect sense to be more concerned about the fly genocide that has been occurring since the dawn of man; these innocent creatures of God that are nearly 700X more complex than a 3-day-old embro. A religious person would argue that the 3-day-old embryo is more important than a fly’s brain because the embryo is a potential human life that will mirror the image of God. The problem with this argument is that in 2011 it is now possible for every cell in your body to potentially become a human being. Every time you scratch your nose you are literally committing a holocaust of potential human life. Now, if you grant the believer’s case that the embryo contains a human soul and the other cells in your body no not, you still run into serious problems. At this stage in their development, an embryo can split in two to create identical twins. Does this mean that one soul has split off into two souls? A further proof that that this “soul logic” is flawed is the fact that at 3-days-old two embryos can fuse together to create a chimera. Many people on earth have been born this way. Does this mean that the soul of embryo-A was extinguished when it merged with embryo-B or vice versa? This is the argument presented by author and neurologist Sam Harris, who concludes, “This arithmetic of souls doesn’t make any sense. It is intellectually and morally indefensible. These religious notions are prolonging the scarcely indureable misery of tens of millions of human beings.”16 Harris elaborates that because of the respect we accord religious faith as the source of our moral code the dialogue is extinguished. He argues that if you think the interests of a 3-day-old embryo trumps those of a little girl with a spinal cord injury or someone with full body burns then your moral intuitions have indeed been obscured by religious metaphysics. “This is a blindness that is very well subscribed in society and it’s a blindness that goes by another name: religious faith. And we’ve been cowed into respecting it.”17 Law-abiding stem cell researchers who shut down their search for cures to countless diseases in accordance to the law of the land have now found themselves in the same moral landscape as Adolf Eichmann did in 1930s-40s Nazi Germany. Certifiably “normal” citizens with the power to affect change, whose moral intuitions have been obscured by the laws and situational circumstances of their respective times the second they turn a blind eye. Rosa Parks’ bus ride that fateful day in 1955 would have been so much “easier” had she allowed that white person to steal her seat. Turning a blind eye is perhaps the easiest thing in the world to do.

Stem cell research is just one case of many where science has undeniably answered a moral question. Anyone who uses reason as their uncontaminated engine of thought can see this. They will also be able to see that science, including the human sciences, is where the real truth of questions of morality are embedded. It is highly probable that at this moment, in a laboratory somewhere in the world, a courageous rule-breaking scientist is about to discover the cure for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s by illegally continuing his or her stem cell research in secret, heroically rejecting the unethical laws that forbid him or her to be engaged in such brilliant work in the first place.

By extension, these absurd laws — that are prohibiting the greatest scientific breakthroughs we could ever possibly hope to achieve — emanate from the same little white house with its beautifully-manicured lawns in the front and back and crisp new flag waving proudly up top. The same house that has seen various charismatic leaders come and go throughout the years, who each had (and have) such divine certainty in their religious faith and beliefs that they are capable of telling two men or two women that their love is fundamentally illegal. As immoral and unethical as these laws are, and as tempted as I am to rank a President “of faith” at 0% right alongside Loughner’s 0% level of empathy, I would be more inclined to place such a leader at around 1% (interestingly, a 1% empathy ranking for a world leader discriminating against stem cell research and gay marriage would mean they rank as the exact opposite of the heroic behavior of Rosa Parks’ 99% on the empathy spectrum, and would still place them in the same morally bankrupt terrain as Adolf Eichmann). It seems blatantly clear that our laws and our faith are not the best places to look for the source of morality, let alone to inspire heroic imagination in its purest form. Even a child could understand this. As physicist Steven Weinberg so famously wrote: “With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.”18

So how do we cultivate more heroic imagination? Certainly not by using divine scripture or obeying the law. Zimburger says it involves just two aspects, “First, thinking of yourself as an active person rather than a passive person: thinking of yourself as somebody willing to get involved; to move off the safety spot of minding your own business; to take a decisive action when the world around you looks the other way. Second, thinking less about yourself, less about your ego, your reputation, less concerned about looking foolish, making a mistake, upsetting someone’s apple cart, and becoming socio-centric – more concerned for the well-being of others or upholding a moral imperative. Perhaps it also entails a dash of optimism, so that you believe you have the power to change something bad by your actions.”19 Zimburger also explained in a 2009 interview with Newsweek that, “To be a hero, what you mostly need is opportunity. We have research that shows that blacks are eight times more likely than whites to have engaged in a heroic act in their life. The reason is simply [that] they have more opportunities. If you live in an urban area, you’re more likely to do something heroic, because there’s more crime. There’s more danger. Whereas if you live in the suburbs, the chance to become a hero is nil.”20

As part of his Heroic Imagination Project (where he is working with young students, local communities, and volunteers to help fertilize heroic imagination and acts of “everyday heroism”), Zimburger explains that, “By getting everyone to think of themselves as heroes-in-waiting, I think that will make it more likely when the opportunity comes that they’ll take action. So we’re experimenting with that idea in schools. We have a curriculum in Flint, Mich., with five classes of fifth graders, and we’ll also get kids to sign up on our website, to say, ‘I’m willing to be a hero in waiting, and while I’m waiting, I’m going to do a little heroic deed every day. I’m going to try to make someone’s life better. I’m going to get someone in my family to stop smoking. I’m going to organize my friends against bullying. And when the opportunity for big heroism comes around to them, we hope they will be better psychologically prepared to act.”21

These new conceptions of the “banality of heroism”, as Zimburger describes it, will be fundamental in reengineering the mythology of heroism in our culture. In this new world filled with invisible dangers and monsters that blend far too easily into the crowd, four everyday heroes from Arizona are rightfully getting their place in the Pantheon Of Everyday Heroes for taking action on that fateful day in Arizona and saving so many lives as a result. As Albert Einstein once said:

.

“The world is a dangerous place, not because of those who do bad things, but because of those who look on and do nothing.”

. [youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3SjCzA71eM[/youtube]

.

FOOTNOTES | 1, 3: The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values by Sam Harris. 2: ABC News. 4, 5, 6, 7: The Rogue Neuron by Andrea Kuszewski. 8: Hitch Looks Back (Foreign Policy, December 2010). 9: The Moral Instinct (The New York Times, January 2008) by Steven Pinker. 10: Morals Without God? (The New York Times, October 2010) by Frans de Waal. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19: Edge: The Third Culture by Russell Weinberger. 18: The New York Times (April 20, 1999). 16, 17: Lecture by Sam Harris at Beyond Belief 2 Conference. 20, 21: The Making Of A Hero (Newsweek, December 2009) by Mary Carmichael.