English archers had their longbows, Old West sheriffs had their six-guns, but Japan’s samurai warriors had the most fearsome weapon of all: the razor-sharp, unsurpassed technology of the katana, or samurai sword. In the documentary Secrets Of The Samurai Sword, NOVA probes the centuries-old secrets that went into forging what many consider the perfect blade. Fifteen traditional Japanese craftsmen spent nearly six months creating the sword that NOVA follows through production, from smelting the ore to forging the steel to sharpening the blade to a keen edge capable of slicing through a row of warriors at one swoop.

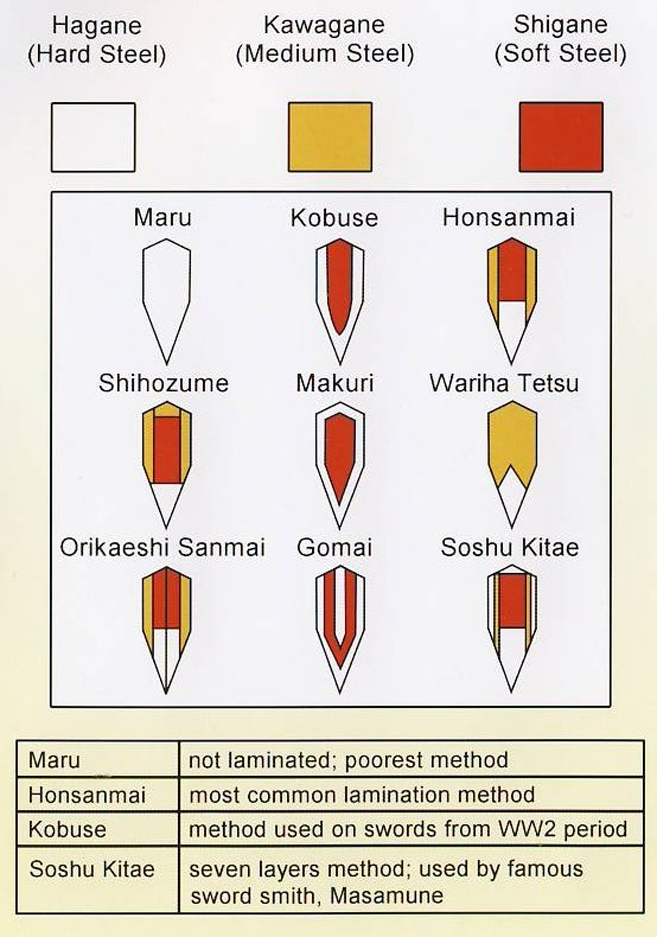

Katanas (samurai swords) are traditionally made from a specialized Japanese steel called tamahagane, which is created from a traditional smelting process that results in several, layered steels with different carbon concentrations. This process helps remove impurities and even out the carbon content of the steel. The smith begins by folding and welding pieces of high and low carbon steel several times to work out most of the impurities. T he resulting block of steel is then drawn out to form a billet. At this stage, it is only slightly curved or may have no curve at all. The gentle curvature of a katana is attained by a process of differential hardening or differential quenching: the smith coats the blade with several layers of a wet clay slurry, which is a special concoction unique to each sword maker, but generally composed of clay, water and any or none of ash, grinding stone powder, or rust. The edge of the blade is coated with a thinner layer than the sides and spine of the sword, heated, and then quenched in water (some sword makers use oil to quench the blade). The slurry causes only the blade’s edge to be hardened and also causes the blade to curve due to the difference in densities of the micro-structures in the steel. When steel with a carbon content of 0.7 percent is heated beyond 750 °C, it enters the austenite phase.

When austenite is cooled very suddenly by quenching in water, the structure changes into martensite, which is a very hard form of steel. When austenite is allowed to cool slowly, its structure changes into a mixture of ferrite and pearlite which is softer than martensite. This process also creates the distinct line down the sides of the blade called the hamon, which is made distinct by polishing. Each hamon and each smith’s style of hamon is distinct. After the blade is forged, it is then sent to be polished. The polishing takes between one and three weeks. The polisher uses finer and finer grains of polishing stones in a process called glazing, until the blade has a mirror finish. H owever, the blunt edge of the katana is often given a matte finish to emphasize the hamon.

Masamune (1264–1343), also known as Gorō Nyūdō Masamune or Priest Gorō Masamune, is widely recognized as Japan’s greatest swordsmith. He created swords and daggers, known in Japanese as tachi and tantō respectively, in the Soshu tradition. No exact dates are known for Masamune’s life and he has reached an almost legendary status. It is generally agreed that he made most of his swords in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, 1288–1328. Some stories list his family name as Okazaki, but some experts believe this is a fabrication to enhance the standing of the Tokugawa family. Masamune is believed to have worked in Sagami Province during the last part of the Kamakura Period (1288–1328), and it is thought that he was trained by swordsmiths from Bizen and Yamashiro provinces, such as Saburo Kunimune, Awataguchi Kunitsuna and Shintōgo Kunimitsu. An award for swordsmiths called the Masamune prize is awarded at the Japanese Sword Making Competition. Although not awarded every year, it is presented to a swordsmith who has created an exceptional work.

.