For the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, it was “a highly pleasurable sensation of warmth all over my whole frame”. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards saw the sinister side in their infamous song from Sticky Fingers: “Please, Sister Morphine, turn my nightmares into dreams.” Christopher Mayhew, the MP who downed a mescaline drink in front of a television camera for a 1955 Panorama programme, told his interviewer that between the beginning and end of his next sentence, he would be “gone for a long time”. The programme was pulled from the schedule. Britain in the 1950s was not ready for time-travelling members of parliament. Nor was it evidently prepared for a frank and cool discussion on the taking of drugs. The issue continues to provide plenty of invective, but little in the way of rational analysis. All the more reason to celebrate High Society, a new show at the Wellcome Collection that tells some uncomfortable truths. The first and most important is that we are all at it. As Mike Jay’s excellent accompanying book tells us, every society is a high society. Whether we are sipping a latte in Bond Street or chewing betel nuts in an Indonesian marketplace, we are forever altering our state of consciousness to get through the day. The idea that there was ever a golden age of sobriety, in comparison to which we have fallen into some kind of disrepute, is shown here to be a dubious one. Drug use stretches too far back, and too widely across the globe, to be considered an aberration of the human condition. It is, the show argues plausibly, a universal impulse.

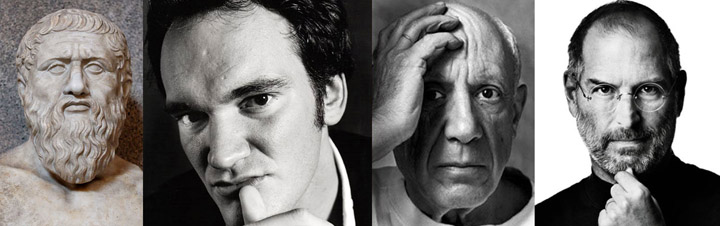

The generation that preceded mine was appalled when the use of cannabis became widespread among its sons and daughters in the 1960s. It might have had a case, were it not so stupefied with tobacco and alcohol (see the television series Mad Men). The repressed societies of the pre- and postwar era were never going to win this battle. An anti-marihuana (sic) poster from the Depression shows a blonde woman looking louchely into the eyes of a man. Warnings are plastered all around her. “What happens at marihuana parties? Weird orgies. Unleashed passions!” It does not, to be honest, sound so bad. So it is not sensible to judge a society by whether or not it takes drugs, but by which drugs it takes, and why. It stops us short when we see, in the Wellcome show, packets of throat pastilles named after their active ingredients: diamorphine and cocaine. There is an air of bathos here, too: cannabis (“weird orgies, unleashed passions!”) was a treatment for diarrhoea in the early 20th century. Artists have always been in the vanguard of drug-taking. So, in the ancient world, were philosophers. Plato’s Symposium, one of the founding texts of western rational thought, was an evocation of a mightily drunken evening. In the 19th century, the unleashed Romantic imagination made merry with exotic substances. Paris’s Club des Hachichins was discussed by most of the city’s literary luminaries, Balzac, Dumas, Flaubert and, of course, Baudelaire. Steve Jobs has never been shy about his use of psychedelics, famously calling his LSD experience “one of the two or three most important things I have done in my life.” (OF INTEREST: Read the Never-Before-Published Letter From LSD-Inventor Albert Hofmann to Apple CEO Steve Jobs). Kevin Herbert, one of the founders of Cisco Systems, told WIRED Magazine, “When I’m on LSD and hearing something that’s pure rhythm, it takes me to another world and into anther brain state where I’ve stopped thinking and started knowing,” Herbert reportedly “solved his toughest technical problems while tripping to drum solos by the Grateful Dead.” The maverick surfer/chemist Kary Mullis, a well-known LSD enthusiast, made it known that acid helped him develop the polymerase chain reaction, a crucial breakthrough for biochemistry. The advance won him the Nobel Prize in 1993. And according to reporter Alun Reese, Francis Crick, who discovered DNA along with James Watson, told friends that he first saw the double-helix structure while tripping on LSD. It’s no secret that Crick took acid; he also publicly advocated the legalization of marijuana. LSD is also currently the golden child of medical research at the moment and gaining huge respect for its research potential, as leading experts believe its chemical structure could potentially cure a host of diseases such as Parkinsons, cancer, post-traumatic stress disorder, etc. Furthermore, the discover of LSD led to the discovery of the neurotransmitter serotonin that jump-started the brain chemistry revolution.

Whether art is improved or not by drug-taking remains one of the recurring debates of our time. Interestingly, the ground has shifted. The 1960s saw drug use summoned in support of social revolution and the creation of a kind of music that had never been heard before. In the present day, it is common to denigrate an album by describing it as the “cocaine one”, as over-hyped musicians play out a familiar trajectory of sudden rise and messy decline.

There is little parallel now between experimentation with a substance and innovation within an art form. Drug-taking is part of a lifestyle of excess, or of desperation. Former drug-users who have survived have become folk heroes – the Keith Richards autobiography will appear on many a Christmas list this year – while those who didn’t make it are merely thought unlucky. Rehab is the tweak in the right direction given to victims who have overstepped the mark. But few great works come out of rehab. In the meantime, those who have encountered serious mind-altering substances can appear anything but glum about the experience. Mayhew looked back on his Panorama-on-mescaline as an overwhelmingly positive day. Talking about it years later, he said he felt as if he had lived in that short interlude through “years and years of heavenly bliss” before coming back round. The video clip of the conversation is riveting. As his interviewer asks him to look at the “dullish red curtain” that is behind the camera, Mayhew dissents. “I see extraordinary gradations of mauve,” he tells his interlocutor, whose sensibleness suddenly seems anaemic. We all, it seems, look for the extraordinary gradations behind the dullish hues. And sometimes we need a little help to get there.

High Society is at the Wellcome Collection, London, until February 27. You can visit their website here.

Source: The Financial Times