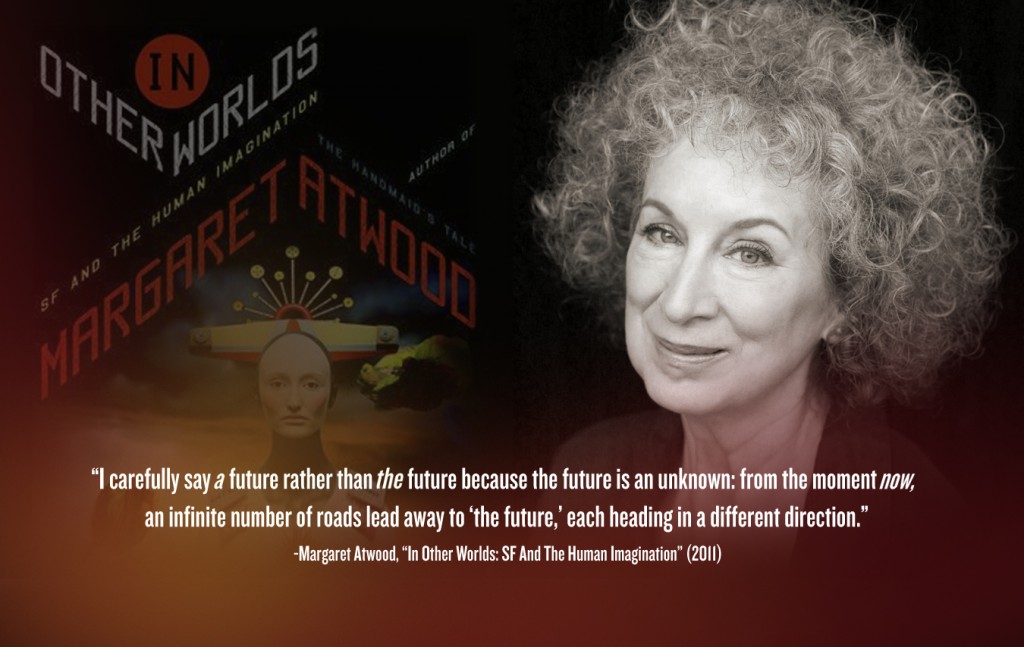

World renowned and award-winning author Margaret Atwood has released her brand new collection of essays entitled In Other Worlds: SF And The Human Imagination. The “SF” being the most gravitational component of the title, seeing as how Atwood has never been shy about her love of pulp fiction and science fiction, but categorizes herself as more so a writer of “speculative fiction” (as she distinguishes them, speculative fiction is more grounded in real history and science than science fiction. She feels that any attempt on her part to write more fanciful science fiction, however much she enjoys reading it, would be unconvincing). As Quill & Quire wrote in their review of the book, “The collection of essays lends Atwood’s distinctive voice and singular point of view to the genre in a series of essays that brilliantly illuminates the essential truths about the modern world. This is an exploration of her relationship with the literary form we have come to know as “science fiction,” a relationship that has been lifelong, stretching from her days as a child reader in the 1940s, through her time as a graduate student at Harvard, where she worked on the Victorian ancestor of the form, and continuing as a writer and reviewer.” The following is an excerpt from In Other Worlds: SF And The Human Imagination:

I entered the sort of modern wonder-tale world we might generally label SF at an early age. I grew up largely in the north woods of Canada, where our family spent the springs, summers, and falls. My access to cultural institutions and artifacts was limited: not only were there no electrical appliances, furnaces, flush toilets, schools, or grocery stores, there was no TV, no radio shows available except for those on short-wave Russian stations, no movies, no theatre, and no libraries. But there were a lot of books. These ranged from scientific textbooks to detective novels, with everything in between. I was never told I couldn’t read any of them, however unsuitable some of them may have been.

I learned to read early so I could read the comic strips because nobody else would take the time to read them out loud to me. The newspaper comics pages were called, then, the funny papers, although a lot of the strips were not funny but highly dramatic, like Terry and the Pirates, which featured a femme fatale called “The Dragon Lady” who used an amazingly long cigarette holder, or oddly surreal, like Little Orphan Annie — where were her eyes? The funny papers raised many questions in my young mind, some of which remain unanswered to this day. What exactly happened when Mandrake the Magician “gestured hypnotically”? Why did the Princess Snowflower character go around with a cauliflower on either ear?

And if those weren’t cauliflowers, what were they?

In addition to being a comics reader, I was an early writer, and I drew a lot: drawing and reading were the main recreations available in the woods, especially when it was raining. Very little of what I wrote or drew was in any way naturalistic, and in this I suspect I was like other children. Those under the age of eight gravitate more easily toward talking animals, dinosaurs, giants, flying humanoids of one kind or another — whether fairies, angels, or aliens — than they do to, say, portrayals of cozy domestic interiors or bucolic landscapes. “Draw a flower” was what we used to be taught in school, and by that was meant a tulip or a daffodil.

But the kinds of flowers we really liked to draw had more in common with Venus flytraps, only a lot bigger, and with half-digested arms and legs sticking out of them.

I revisited my early non-naturalistic tendencies during a recent trip I took through my own juvenilia, or what survives of it. When I say “juvenilia,” I’m not talking about the precocious teenage poems of William Blake or John Keats, but about things I was doing in the mid- 1940s when I was six or seven. They centred around my superheroes, who were flying rabbits. Their names were Blue Bunny and White Bunny, and they were modeled upon two unimaginatively named real-life stuffed animals who did indeed go flying through the air, propelled by an age-old technology called “throwing.” But it wasn’t long before these feeble heroes morphed into two tougher creatures called Steel Bunny and Dotty Bunny, who flew in a more conventional superhero way, by means of capes. Steel’s cape had bars on it, Dotty’s had dots. So far, so clear.

My superhero rabbits were pale imitations of my older brother’s more richly endowed creations. It was he who invented flying rabbits — extraterrestrial flying rabbits. His were equipped with vehicles and advanced technologies — spaceships, airplanes, weaponry, the lot — and did battle not only with their hereditary enemies, the evil foxes, but with robots and man-eating plants and lethal animals. The planet where my brother’s rabbits lived was called Bunnyland; mine inhabited a more mysterious place called Mischiefland. Now what impelled me to name it that?

The rabbits in Mischiefland led a disorganized existence. They floated around by means of balloons — unavailable during the Second World War and thus of great fascination to me. Also I had by this time read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, in which the wizard goes soaring away in a basket lifted by an enormous hot-air balloon. I allowed not only my rabbits but their pet cats to be levitated in this way. (I was not permitted to have a cat, and longed for one, so my rabbits had a lot of them.) The rabbits ate nothing but ice-cream cones, rare and desirable during wartime and the several lean years that followed. And they did tricks: specifically, a lot of twirling in the air, with the aid of their flying capes. They were only fitfully interested in shooting guns, pursuing criminals, saving the world, and so forth, though they did eject the occasional bullet from the occasional handgun, smiling eerily while doing it. But mostly, it seems, they just wanted to have fun and fool people.

Where did we kids discover the knowledge of flying capes, superpowers, other planets, and the like? In part, through the primitive comic-strip superheroes of the times, the most popular of which were Flash Gordon, for space travel and robots; Superman and Captain Marvel, for extra strength, superpowers, and cape-based flying; and Batman, who was a mortal, with a non-functional cape — one that must have encumbered him somewhat as he clawed his way up the sides of buildings — but who nonetheless shared with Captain Marvel and Superman a weak or fatuous second identity that acted as a disguise. (Captain Marvel was Billy Batson, the crippled newsboy; Superman was Clark Kent, the bespectacled reporter; Batman was Bruce Wayne, the very rich playboy who lounged around in a smoking jacket.)

Those — crossed with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a dollop of Greek mythology, and our one small book on the solar system —were probably the sources of our core ideas. The solar-system book was sedate in and of itself, but I should point out that at that time the planets were still relatively unknown, and thus still open for population by extraterrestrial life, which in our case leaned heavily toward hostile humanoid aliens with one eye and three-fingered hands, animals with razor-sharp teeth and nasty lurking and disemboweling habits, fish that could shoot electric rays at you or gas you to death, and plant life equipped with poisonous prickles or bulbs, or whiplike tentacles and rapid digestive systems. As our father was an entomologist and all-round naturalist, we also had ample access to scientific drawings of, for instance, pond life under the microscope, which may have contributed to our ideas of what Martians and Venusians and Neptunians and Saturnians should look like.

As for disguises, I note that our rabbits seldom felt the need for them: being short and young, we were our own Billy Batsons, and I assume that projecting your child ego onto a flying rabbit was enough of a dedoublement for us.

But where did the creators of the superheroes in the funny papers get their own ideas? I now find myself wondering.

For your own copy of Margaret Atwood’s In Other Worlds: SF And The Human Imagination simply head over to Amazon. You can read Slate’s review of the book by visiting Slate.com. Atwood is one of the most prolific writers in the world, and among the international recognition of her work are the following awards: a two-time recipient of the Governor General’s Award; Companion of the Order of Canada, the Guggenheim fellowship, Los Angeles Times Fiction Award, Arthur C. Clarke Award for best Science Fiction, Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Government of France’s Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Helmerich Award, the 2000 Booker Prize, and many more. To learn more about the extraordinary work of Margaret Atwood CLICK HERE, and be sure to visit her website at MargaretAtwood.ca. (In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination copyright © 2011 by O.W. Toad Ltd. Published by Signal, imprint of McClelland & Stewart Ltd.)